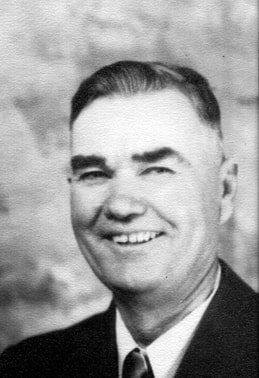

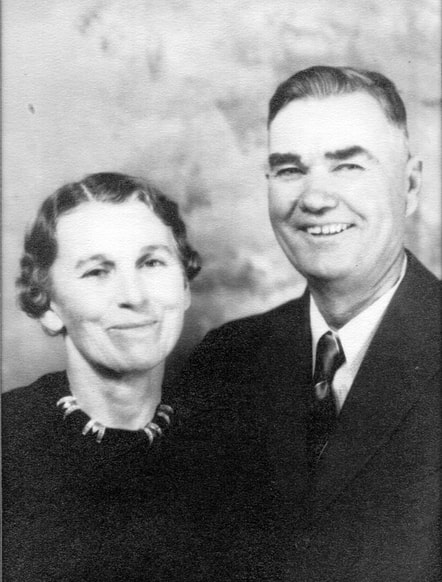

Troy Blooming Cowan Troy Blooming Cowan First, how do I connect with Troy Blooming Cowan? Troy's mother was Eliza Evans. Eliza's sister was Nancy Elizabeth Evans who married William Artice Cook. William and Nancy were my 2nd-great-grandparents. (Troy is my 2nd cousin 3 times removed; my Mom's 1st cousin 2 times removed, my Grandma Brooksie's 1st cousin 1 time removed). The first time I heard of Eliza Cowan was in a letter written by John Henry Evans (Eliza and Nancy's father) to Nancy and William on January 6, 1882. John mentioned that he had received a letter from her. It is interesting to note, that my Grandma Brooksie also had a brother named Troy Blooming Ketchum. I've always wondered where that name came from! Porter Long, who has submitted all the information on the Cowan family and is a descendant of Troy's said that Blooming Stillwell helped raise the Cowan's and was connected in some way. The following story was submitted by Porter Long, his research on his line of the family can be found on familysearch.org and the story "Life on the Range" is found on the Library of Congress website as well. "Life on the Range" Range lore

Phipps, Woody Rangelore Tarrant Co., Dist. #7 Page #1 FEC Troy B. Cowan, 59, was born on his father's 'CAS' ranch, in [Erath?] co., Tex., Aug. 1, [1878?]. He leanred to ride early, and was employed on three trail drives from Anderson co. to West Texas counties, in 1884, '86 and '92. Following the drive in 1891, his father established a ranch in [Lynn co.?] Until 1910 the ranch consisted of four sections, at which time it was out into homesteads and rented to farmers. Cowan was never employed by another ranch, but remained with his father until his death in 1936, at which time he inherited the property. He now resides in Lubbock, Tex. His story: “Well, I reckon I've rode the range! In fact, I believe I even hit the trail younger than most anyone else in history. I had just turned six when my dad took me on a trail drive from Anderson county, in East Texas, to the Panhandle. “To start at the beginning, I was born August 1, 1878, on my dad's '[GAS?]' ranch in [rath?] county. He run from 100 to 1,000 in that iron. The difference come about an account of him being such a dealer. He'd sell, trade, or buy, at the drop of a hat. About the only thing I recollect about the [rath?] county ranch was me learning to ride a hoss. They worked with me 'til I could ride pretty good. I could ride as good as the baby rider they had here in the Stock Show. I believe his name was Kidd; and he'd been riding since he was three years old - riding in a wild West show. “I could ride good enough that, when I was six, my dad took me and went to Anderson county, where he bought around 1,500 three and four-year-old steers, he took on some cowpokes, and we started West with the herd. Of course, I didn't do any night riding, nor roping. The only thing I done on the drive was to hustle the stranglers and help keep the herd together. C12 - 2/[?]/41 - Texas 7 That's an important thing on any cattle drive, and keeps the cowpokes busy doing it. “Since I was so young, I can't recall any names of rivers, counties, or anything else. I do recall, however, crossing a lot of rivers, creeks, and so on. You see, this drive was in the Fall and all the rivers and creeks were up. We'd drive to find a place to ford them before we crossed them. If a ford couldn't be found, then we'd make the herd swim it. Dad never did like to make his critters swim, because there was quite a bit of danger in losing some of them. That first drive, though, never lost a head, and we run it clear to Haskell county. “When we got to Haskell county, there wasn't but one fence in the whole county. It was a drift fence and run along the south and east sides of the county. We tried to fence up some acreage for winter holding, but failed. Dad fenced two sections; and any time anybody wanted to go through, they just stomped the fence down. You see, they'd been used to going in a straight line to wherever they'd started, so when they come to dad's little old fence they'd have their hosses push on the fence posts 'til they got a little weak and bent over, then they'd tear them down. “The rest of that country was open everywhere. In fact, I don't recall but two other herds of cattle in there, and they belonged to two big outfits. One was the '[W?] Cross', made like this: . The other was called the 'Flooey De [Mustard?]', the iron made like this. “Now, we never did see the owners of these outfits, and I don't know that I ever did hear who they were. I just don't recall 3 it, if I did. We did all pitch together, though, when we went on roundups. The men from both outfits come and we all went together, rounded all tue cattle together into one holding spot, then cut out what belonged to each other, and drove them to our headquarters. Of the two outfits there, the Flooey De [Mustard?] was the biggest, because there were thousands of them there. “We all followed the same practice of branding in the Spring and selling in the Fall. Because dad never did establish him a headquarters, with buildings and all, he was called a 'Stray Rancher'. “The middle of '86, or sometime along in the Summer of '86, dad sold his cattle to some fellow by the name of Jeff [Bewdry?], and we went back to Anderson county. This time, though, we went back to Erath county and got the rest of the family. I had three sisters, Lula, Bertie and Annie. They could all ride and rope, and dad just brougat them along. My mother died while we were in Haskell county and was buried before we got word of it, because in those times there was no mail, telegraph, telephone, nor anything else for a man that didn't establish a place for himself near a place where he could get mail. “When we got to Anderson county, dad made the rounds, made his deals, then we rounded up the cattle we were to drive west. I don't know whether he knowed where he was going with the herd or not. I don't believe dad did know, though. I just believe he had it in mind that he's settle on some place of land that looked good to him, when he came to it. Now, that's how plentiful land was in them days. “I don't recall the brands dad bought from in Anderson county 4 but I do know that he road branded every head with a '3'. You see,whatever brand the cattle had before he'd brand a '3' right along with them, and that way people'd know they were his. “This time, we took a little different route and, in about four weeks, we [landed?] the herd in Borden county. That was certainly the most God-for-saken county ever I saw when we got there. No neighbors for miles and miles. You'd hardly see a stranger a month. That was how unsettled Borden county was, then. There was wild game a-plenty everywhere. Prairie chickens, which are now out of existence, were so plentiful then that they were a pest. They flew in big flocks, like wild geese. “After a couple of years, though, other cattlemen began to drive their cattle in, and the country began to settle up. [Dad?] never did like to have so many other cattle in with his stock, and it wasn't so long 'til he sold out to some man that wanted to go into the Territory. “[We?] made another trip then, back to Anderson county, and dad bought another herd. This time, though, he got 3,000 head, and we drove it back on about the same route we used going into Borden county. My sisters took a big hand in this drive, and I stood night herd with the rest just an I was supposed to do. I was about 13, then, and rode and roped with the rest of the cowpokes. “While my sisters rode and roped with us, they done all the cooking, so they really didn't take as big a hand an they could've if they'd been allowed away from the cooking end of things. “Somewhere along in Eastland county, I was standing night herd, and the night was actually black as pitch. You couldn't see your hand, it was so dark. I have a good [picture?] of that 5 night, as I rode along about 25 foot away from the herd, singing to the cattle to keep them quiet. Then, all of a sudden, the herd jumped up and started running right towards me. But a sound had I heard—-nothing. “You know, in a stampede, there's always something to start the herd to running, some kind of a noise. This time, it wasn't raining, nor anything else. Everything was just as quiet as could be, then this herd just jumps up and starts running. Things could have been better for me if they'd have started some other way, but they run towards me. At first, I turned my hoss and tried to ride away from the herd, but then my better sense got the upper hand, and I turned around and tried to find the leaders of the stomp. I finally, after letting the front of the herd come alongside me, singled out a couple of the leaders, and went to one of them and started to pushing and slapping him with my rope. Pretty soon, he turned a little to get away from that rope, and then some more. “The result was that he [started?] a mill, but the night was so dark that the most of the herd just ran on by. Those that I got into a mill finally run down, then laid down to rest. The next morning, we started out to round up the ones that had got away. We were four days rounding up all we could find, and when the tally was made there were more than 40 head missing [that?] we never did get. “We stayed right there on that spot for a week, looking for the rest of them, then moved on. We wound up in Howard county. and dad made his headquarters right by the old Tahoka Lake Trail. You see, there were no roads anywhere in that part of the country in them days. If you wanted to go somewhere, and wanted something to guide you, you took a cattle trail. They all had names, and 6 this one was the one ranchers used to get up into the deep Panhandle. It led right by Tahoka Lake. “Them cattle trails looked right queer after you'd seen roads other people used. You see, no matter how big a herd you had, nearly all the cattle followed a leader, and that made a lot of trails right together. Now, any number of herds on the trail drive passed by our place. There'd be from 2,000 to 5,000 head in the drive, and they'd make from 200 to 300 separate trails, or paths, right together where the they'd followed a leader. I'm sure you've seen cow trails in a pasture. Well, just picture 300 of [them?] going the same way. That's the old trail drives for you. “I don't recall the year, but a couple of years later, we moved to Lynn county; and dad established a regular ranch with buildings, barns, corrals, and everything he needed. He proved up four sections of land, and made it his own. The rest of his grazing, he rented. “Along about 1910, he cut his place up into homesteads and rented them out to tenants. That finished the ranching business for him. And, it wasn't so long 'til the rest of the ranchers followed suit and done the same. Today, there's only three ranches in Lynn county and they're not wholly in Lynn either. Just a part of them. “Now there's the 'T” ranch, owned by [C.C. Edwards??] of Fort Worth. I reckon there's 140 sections in his spread. The 'Spade', better known as the 'Yellowhouse Ranch', has a part of its ranch in Lynn, and the 'S' ranch. The 'S' spread was owned by C.C. Slaughter, but his heirs have it now. The iron is a lazy S, like this: 7 “Naturally, from living around them ranches, I got to know quite a few people from there. I got to know the 'S' people better. There were a couple of cowgirls on the 'S' Spread, that could really ride and rope better than any woman ever I seen. Their names were Ethel and Bess Andres. They were what I'd call boys in girl's clothing, because they sure took the place of a boy on the range. I'm not talking from hearsay; I'm talking from seeing them do it. [Why?], I've seen them riding after a cow critter, and come to a place where they had to do some fancy riding, and you could see light between them and the saddle. You know, they could cut out as well as most men. Of course, they didn't ride no [buckers?]. They rode the gentle ones, but they rode them fast when fast riding was called for. “Now, in cutting out, you've got to ride your hoss into the herd, and make a cast at the critter you want out. You don't rope it, you just do that to show your hoss what one you want, and he's been trained to chase it out of the herd to where you can lasso it and throw it. [Well?], while in a herd, your hoss will have to do a lot of in and out dodging. The rider has to know the trick of following the hoss's motions and so fixing themselves that they'll stay in the saddle when a hoss turns real sudden. The way you do that, you keep your eye on your critter, and when it turns, fix to turn that way because your hoss is going to turn that way, and if you're not already fixed to turn you'll find yourself on the ground. Or, if in a herd, you might get stomped to death. It's happened many a time just that away. “I'll just give you an example of what happens when you don't know to watch the critter you're after. I went over to 8 the Lazy S one day; and, to give me a good time, the foreman called a fellow out to him, pointed him out a steer to get and told him to use his hoss to get the steer with. Now, this man had this here '[TB]' consumption. He was out in the west to get his health back. He'd told the foreman that he could ride a hoss, and the foreman'd given him a job. This fellow, who'd been a tobacco salesman before, didn't have any cow sense, but was right willing to work. The only way he was ever to get any cow sense, the foreman figured, was to put him right into the work, so that's what he did. “Well, on the day I was there, he decided to learn his to cut. “Now, he hadn't really handicapped him when he sent him after that steer, because he'd given him the very best cutting hoss anywhere, the foreman's own hoss. He was easy to ride, too. Well, the greener mounted him, and rode him out into the herd. He slapped the critter with his rope, and the hoss took after him. Well, the hoss jumped this way and that, trying to head the steer off every time he headed any way but out, and the greener nearly fell off at every jump. He tried to watch the hoss and lean with the jump, but when you've got a good cutting hoss in the herd, you just can't follow it that away. This greener would have been in that herd yet if it hadn't have been that his hoss was good enough to bring that steer out of the herd without help from anybody. [We?] boys just roared and roared. Some of us laughed so hard at [?] that greener that our sides were sore for a spell after that. “The cowpokes just naturally all loved to pull pranks that away. This same greener had a hard time for a spell around there, 9 for I was over a couple of days later to the roundup, and they pulled another on him. Just before supper the greener come in, dog-tired, and laid down under the chuck wagon to rest. Out in the open like that, where the air's clean and pure, there's [not?] much racket, and the work's all hard, it's mighty easy to sleep. And, that's what mister greener done. Some other [cowpokes?] came in, and they saw him there. One of them decided to [prank?] him, so he gets a saddle and takes it over to the greener. The greener don't hear him coming, but snoozes right on. The cowpoke puts the saddle right up close to the greener's head and starts rocking the saddle from side to side, hollering, 'Whoa! whoa! whoa!' That greener must have thought he was still in the saddle, because he came straight up and bumped his noggin an the reach [pole?]. Bumped it hard, too. [We?] had another laugh on him, then. “For supper that night, the cooky'd roasted the [smelts?], the tongue, ribs and so on, over the fire. Now, the greener hadn't been out before where he couldn't get any wood, and he didn't know that when you can't get wood on the range, you used cow chips for your fire and was glad to get them. He was a little put out by the cow chips, and we could tell it. He wasn't saying anything, though, just looking. Well, one of the boys decided to fix him up some more. He takes a section of ribs, finds him a cow chip to lay them on, then proceeds to use it us a plate. He'd tear off a hunk, then lay them ribs back on the chip while he ate the bit he'd tore off. The greener couldn't take it, he left the chuck wagon, got on his hoss and rode off for a piece. We had another laugh on him. “You know, when a greener hit any spread, he sure had a hard 10 time for [awhile?], because the cowpokes'd ride him 'til he caught on to [all?] the tricks. By that time, there'd be another come on, and [he?] could join in on the fun. “I reckon this about catches me up. I'm living in [Lucbuck?], if you want me for anything. Library of Congress [Troy B. Cowan] http://www.loc.gov/resource/wpalh3.37010810

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

AuthorMy name is Vicky, and after researching my family history since 1999, I have found amazing stories that need to be told. I hope you enjoy them as much as I have! Archives

May 2023

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed