John Richardson

(1628 - November 16, 1679)

Martha Mead

(November 08, 1632 - November 20, 1695)

(1628 - November 16, 1679)

Martha Mead

(November 08, 1632 - November 20, 1695)

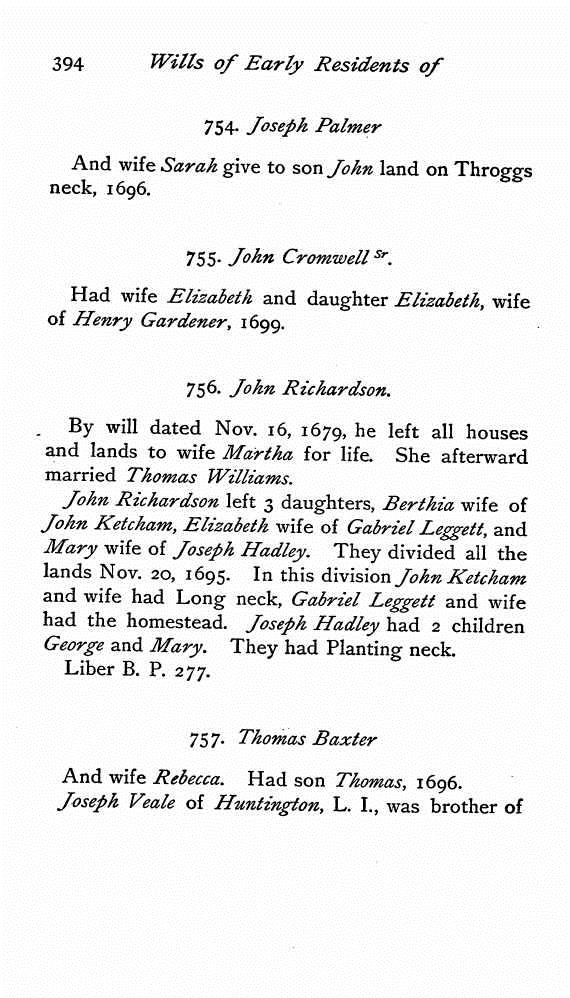

John Richardson was born in 1628 in Essexshire, England, parents unknown. He passed on November 16, 1679 in Stamford, Fairfield, Connecticut. John married Martha Mead in October 1654 in Stamford, Fairfield, Connecticut. Martha was the daughter of William Mead and was born on November 08, 1632 in Lydd, Kent, England. She passed on November 20, 1695 in Stamford, Fairfield, Connecticut.

John and Martha's children:

1. Bethia Richardson, m. John Ketchum.

2. Elizabeth Richardson, m. Gabriel Leggett

3. Mary Richardson, m. Joseph Hadley

John and Martha's children:

1. Bethia Richardson, m. John Ketchum.

2. Elizabeth Richardson, m. Gabriel Leggett

3. Mary Richardson, m. Joseph Hadley

Martha Mead

(November 08, 1632 - November 20, 1695)

The following story was published in Martha Mead by Lee Meade, 1996 Mead-e Family Newsletter:

It is generally believed that life was simpler during the early days of American colonization. The settlers worried about attacks by Indians, but they were few and far between. They had concerns about the weather, but for the most part, the Connecticut climate was mild and crops grew well. Everyone followed a stoic lifestyle, working from dawn to dusk during the week and socializing between intermittal breaks in the day-long Sunday worship service.

However, that wasn’t always the way it was. At times, there was social intrigue too that stirred the community to dramatic proportions.

Martha Mead, believed to be the only daughter of William and Philippa Mead of Stamford, unwillingly became the subject of one of the most controversial legal cases in 17th Century New England.

If early records are accurate, Martha was born in the town of Lydd in County Kent, England, about 1632. She had an older brother, Joseph, and younger brother John.

After landing at Boston, the Meads moved first to a new settlement at Wethersfield, Conn., and then on to Stamford, where William was one of the community’s first landowners.

She was just 9 years old when her father received a home lot and five acres of land as one of the original 42 settlers in Stamford. Twelve years later, she married John Richardson of Stamford and seemed to be well on her way to becoming a typical New England housewife.

But there was trouble and considerable tribulation just around the corner for Martha and her family.

Martha had a problem. Several months prior to her wedding, she discovered she was pregnant. She told her parents, her brothers and fiancé.

“I don’t know how it happened and I don’t know who the father is,” she confessed to her probably disbelieving audience.

As they attempted to sort through the facts, Martha recalled there was a day while she had been working as a domestic servant in the home of one of the Stamford residents when she lost consciousness during an epileptic seizure. When she came to, she had been taken to a bedroom in the house and, she suggested, may have been raped. There were only two men in the house at the time, and, although Martha knew both of them, she could not identify which one may have been her attacker.

Her husband acknowledged he was not the father, but he did not want her to be castigated in the eyes of the community, so he suggested they move to Roxbury, Mass., a small town near Boston, and live there until after the baby had been born. Outside the immediate family, nobody knew the real reason for the move.

The baby was born, but died within its first month of life, and Martha and John returned to Stamford.

All of this had taken place in 1653, but a year later a rumor surfaced in Stamford that Martha had been pregnant at the time of her wedding, that she had given birth to a baby in Massachusetts and the baby had died under mysterious circumstances.

One can only imagine the excitement the report stirred in the small, conservative Puritan town. For weeks, the gossip about Martha Mead was spoken in hushes. Then it broke into the open, and was brought to the attention of the magistrates in New Haven, the colonial capital of the province.

When Martha was confronted with the charges, she denied she had ever been pregnant. However on Oct. 18, 1654, a Court of Magistrates was called in New haven to hear the case, and “take whatever action it deemed appropriate.”

Present at the hearing were Theophilus Eaton, Esq., Governor of Connecticut; Stephen Goodyeer, Deputy Governor, and Magistrates Samuell Eaton, Francis Newman, Benjamin Fenn and William Leete.

The charge was that “Martha Mead, now the wife of John Richardson of Stamford, was guilty of fornication, proued by her being with child some months before marriage, and that to avoyde or stopp reproach, her husband had carried her to Roxbury in the Massachusets, where she was deliuered of a child in January last, at the house of Mr. Joshua Hughes, wch child luied aboute or aboue a moneth and then dyed, but how and in what manner, the court though worth inquirie.”

Richardson admitted his wife was with child before marriage, that he knew of her condition, but denied he was the father. He said he took her from Stamford to Roxbury before childbearing to avoid the public shame.

“When did you marry Martha Mead?” the Court asked. “And when did she have the child?”

“I married her at the latter part of wheat harvest,” Richardson replied. “The baby was born in January. It passed away less than a month later. We returned to Stamford, but thought there was nothing to be gained by opening our personal discomfort.”

Martha confirmed she had been with child before her marriage, but boldly declared, “I neither did – no do – know who is the father.” “I was in a fit of swooning in my Master’s house in Stamford,” she explained. “While I was unconscious, I was carried to a bed in another room and I was taken advantage of. When I came to, I saw Joseph Garnesy in the room, but I do not know who it was that abused me.”

The court read the written evidence and heard the verbal testimony of several Stamford witnesses. In addition to Garnesy, one other man, John Ross, had been in the house when the incident allegedly occurred. Her brother, Joseph, and several townfolk, including goodwife Knapp, goodwife Stocke, goodwife Buxton, goodwife Webb and goodwife Emry, testified Martha had been subject to “fainting and swooning fitts, mixed with short distempers of frenzy.”

In its findings, the court ruled it could do nothing else but find Martha Mead Richardson “guilty as charged, both of knowne fornication and continewed impudent lying, beeleeuing that no woman can be gotten with child without some knowledg, consent and delight in the acting thereof, and that she deserves to be publiquely and severely corrected by whipping, but considering she is now great with child, and according to testimony apt to fall into the forementioned fitts, with due respect to her condition it is ordered, that tenn pounds be paid as a fine to the jurisdiction within a years time for her heinous miscarriages.”

The court acknowleged that “John Richardson, and her brother, Joseph Mead, did before the court as sureties ingage, and entered into a recognizance of fifty pounds for ye same, and vnder the same penalty promised and bound themselues that, betwixt this and the court of magisrats in May next, they would bring a satisfying certificate from Roxbury concerning ye death of ye child, both wch being duely pformed their ingagmnt and recognizance are voyd & discharged, but till ten stand in force, and in ye meane time if she duely acknowleg her sinn and truly declare who is ye father of the child, the court will consider of some further mitigation.”

Final disposition of the case lingered on through three additional hearings.

On May 28, 1656, Joseph Mead and John Richardson appeared in court at New haven and acknowledged “payment of the fine of tenn pounds which was not required, but they desired forbearance till next Michaelmas when they then see it paide.” The court granted their request.

On Sept. 27, 1657, William Mead, Martha’s father, and his youngest son, John, appeared in court petitioning for abatement of two fines. John had been fined ten pounds in a subsequent slander and harassment action, brought by a Stamford neighbor while the fine against Martha and levied against Joseph mead and John Richardson remained unpaid.

The court considered both and granted that “half of each should be abated, provided the other half be paid forthwith.”

The issue was finally put to rest when Joseph brought in two “milch cowes” which he offered as payment of the fines. The court, following a recess to determine the value of the two cows, argued the “cowes” were worth “only eight pound tenn shillings,” but “in fauour to them (Joseph Mead and John Richardson),” the court would accept the cows as payment, and acquit and discharge the fines.”

As a tragic aftermath, Martha Mead and john Richardson also lost her second baby, who like the first, died early in its infancy. The Richardsons never had any other children of record and shortly after the case was resolved moved from Stamford to nearby Rye, NY.

Although there is nothing to suggest the events were connected, both Joseph and John also left Stamford in 1657, crossing Long Island Sound to become involved in the founding of the town of Hemstead, Long Island. However they liked Connecticut better and two years later returned with their families – not to Stamford, but to its next door neighbor, the new settlement of Hogs Neck, later to be known as Greenwich.

NEWSLETTER EDITOR’S NOTE: There is recent information that Mary and John Richardson did live in Westchester County, New York, and had three children, all girls. The three were Bethia, born 1654, and married to John Ketcham; Mary, born 1655, and married to Joseph Hadley, and Elizabeth, born 1656, and married to Gabriel Leggett. As we know from the court records above, Mary was in trial in new Haven in Oct. 1854 and was pregnant at the time. Thus, it is possible, although not proved, that Mary’s second child did live and was named Bethia. John Richardson died in 1679 and Martha remarried Capt. Thomas Williams. They had no children.

=====================================================================================================================

Soon after her conviction, Martha and John, to avoid further reprisal, moved to nearby Westchester County, in New York.

There John Richardson, in partnership with Edward Jessup, bought Indian lands from the local Indians, the Shonearoekite and eight other tribes This patent dated April 26, 1666 was known as West Farms Patent and was granted to them by King James. The name was given to describe its location relative to the other settlements in Connecticut.

The boundaries of their land was the Bronx River to the East; East River to the South; Harlem River and the Hudson Rivers to the West; and the township of Yonkers on the North. Within a year Edward Jessup died and willed his land to his daughter Elizabeth Hunt, the wife of Thomas Hunt. Today Hunt’s Point on the East river is named for this family.

In 1873 West Farm was removed from Westchester County and annexed into New York City. In 1898 it was made a burrow of New York City, known as Bronx. A descendant family through Elizabeth, the daughter of John and Martha, still owns land in Bronx. Their name is Tiffany.

John and Martha had three daughters: Elizabeth who married Gabriel Leggett; Mary who married Joseph Hadley; Bertha who married Joseph Ketcham.

For further reading, a more detailed story can be found in the book "Early Settlers of West Farms Westchester County, NY" by Rev. Theodore A Leggett. John Richardson is first mentioned on page 10 and mentioned throughout the book. A copy can be downloaded below and also be downloaded from http://archive.org

| earlysettlersofwestfarms.pdf | |

| File Size: | 6670 kb |

| File Type: | |

Proudly powered by Weebly